Sheep are ruminants, meaning they have a ruminant digestive system and process the foods they eat in a unique way. If you have sheep (or plan on getting a flock in the future), you will need to understand the way their digestive system works.

Let’s take a close look at a sheep’s digestive system and learn how it functions in sheep, why they chew cud, and how their unique stomachs help them process their fibrous diet.

What is a Ruminant?

A ruminant is a hoofed mammal with a special digestive system that lets them more effectively use energy found in fibrous plant material. The digestive system of a ruminant can ferment the food the animal eats and give the animal precursors for energy that the animal needs to use. Livestock animals that have ruminant digestive systems include sheep, cattle, and goats.

How Does the Ruminant Digestive System Work?

An understanding of how the ruminant digestive system works will help you understand the best ways to feed and care for your sheep. When an animal has a ruminant digestive system, it is able to get the greatest level of energy from high roughage foods, such as forages.

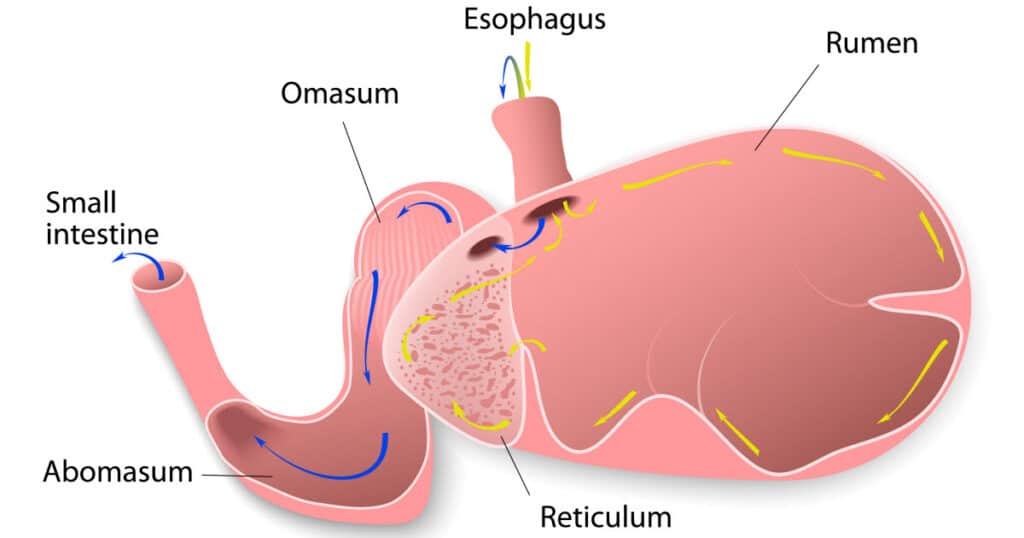

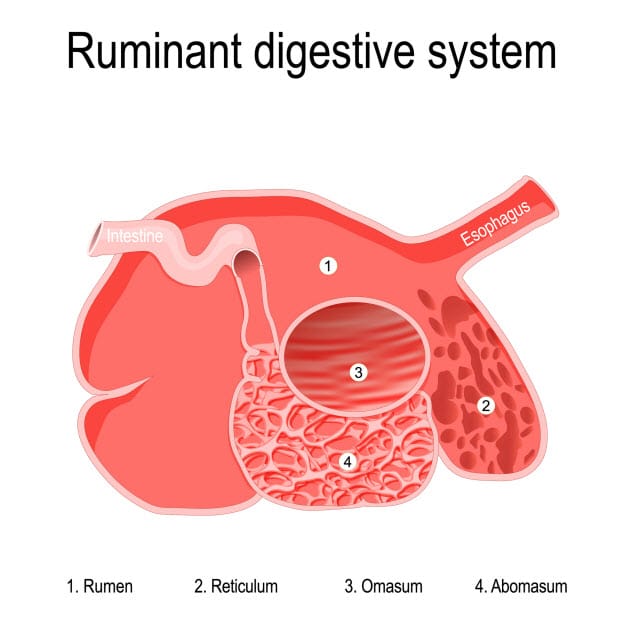

The most important parts of the ruminant digestive system are the tongue, mouth, esophagus, salivary glands (which create saliva that help to buffer rumen pH), a stomach with four compartments (the rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum), gall bladder, pancreas, small intestine (which includes the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum), and large intestine (which includes the cecum, colon, and rectum).

Eating

During grazing and when eating harvested foods, ruminants use their mouths (oral cavities) and tongues. If you look inside a ruminant’s mouth, you will find that the roof has both a hard and soft palate, and that there are no incisors in the upper jaw.

When the animal chews, the incisors of the lower jaw grind against the hard dental pad. The molars and premolars are the same on the upper and lower jaws. The sheep’s teeth crush plant material and grind it while chewing and during rumination.

Saliva is important in the chewing and swallowing process. It provides enzyme for the breakdown of starch (salivary amylase) and fat (salivary lipase). Saliva also recycles nitrogen to the rumen. The most important part that saliva plays is the buffering of pH levels in the rumen and reticulum. Chewing stimulates the production of saliva.

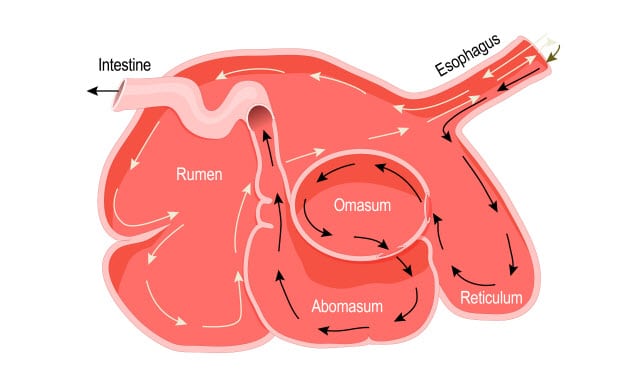

A bolus forms when feed mixes or forage mixes with saliva. The bolus is transported from the mouth to the sheep’s reticulum through the esophagus, which is a tube-shaped passage. Differences in pressure and muscle contractions bring these substances down through the esophagus and into the reticulum.

A ruminant will usually eat very quickly, often swallowing a lot of their food without fully chewing it. The esophagus of an animal with a ruminant digestive system is different from other animals in that it allows for bidirectional movement.

The cud is regurgitated for the animal to chew it more.

Rumination

When the animal chews its cud, this is the process of rumination. During rumination, the food that has been regurgitated is mixed with more saliva and chewed more. After that, the animal swallows it again and it then goes to the reticulum.

After that, the solid part of the food slowly travels into the rumen, where fermentation takes place. Most of the liquid part will quickly travel from the reticulorumen and make its way into the omasum. After that, it goes into the abomasum.

There will be a solid part that is still in the rumen, which usually stays there for up to 48 hours. It transforms into a dense mass in which microbes can make use of fibrous foodstuffs. This is what creates precursors for energy.

Understanding the Ruminant Stomach

Sheep, as well as goats, cattle, antelope, and deer, are true ruminants. This means that they have a stomach with four compartments. These compartments are the:

- Rumen

- Reticulum

- Omasum

- Abomasum

Nearly 75% of the animal’s abdominal cavity is taken up by this four-compartment stomach. Almost all of the abdominal cavity’s left side and some of the right side is occupied by the stomach.

Ruminant Stomach Compartments

The compartments of the stomach have different sizes. 84 percent of the stomach’s total volume are the rumen and reticulum. The omasum is 12 percent, while the abomasum is 4 percent. The largest compartment of the stomach is the rumen. In a mature cow, it can hold as many as 40 gallons.

The reticulorumen houses a huge number of microorganisms (“rumen bugs” or microbes). These include protozoa, bacteria, and fungi. These “rumen bugs” are crucial for fermenting and breaking down the cell walls of plants, rendering them into carbohydrate fractions and creating volatile fatty acids.

Examples of these volatile fatty acids are priopionate (crucial in glucose synthesis), acetate (used in fat synthesis), and butyrate.

Rumen

Sometimes you will hear the rumen called the “paunch.” It has lining of papillae needed for nutrient absorption. Muscular pillars divide the rumen into different sections, which are the:

- Dorsal

- Ventral

- Caudodorsal

- Caudoventral sacs

When the rumen houses microbial fermentation, it behaves as a fermentation vat. The rumen is where approximately 50 or 60% of soluble sugar and starch is digested. Microorganisms in the rumen (mostly bacteria) help digest cellulose found in plant cell walls, as well as complex starch. They also synthesize vitamin K and B vitamins, as well as synthesize protein from nitrogen that has nonprotein sources.

The pH of the rumen is usually between 6.5 and 6.8. It has an anaerobic environment (this means that it doesn’t have oxygen). The are gases generated in the rumen, include methane, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen sulfide. The gas will move to the top of the rumen, sitting above liquid.

Reticulum

You will sometimes hear the reticulum being referred to as the “honeycomb.” This is because it looks a bit like a honeycomb in what its lining looks like. The reticulum is beneath and in the direction of the front of the rumen. It is against the animal’s diaphragm.

Omasum

A short tunnel connects the omasum and reticulum. The omasum is spherical in shape, and is sometimes called the “many piles” because it has so many folds. These folds expand the surface area and provides more area for the absorption of nutrients. Absorption of water happens in the omasum.

Abomasum

The ruminant’s abomasum is referred to as its “true stomach.” It is the compartment most similar to a nonruminant’s stomach. Digestive enzymes and hydrochloric acid are made in the abomasum. The abomasum also brings in digestive enzymes that come from the pancreas.

These include pancreatic lipase (this is needed for breaking down fats). These secretions are necessary for getting proteins ready for absorption processes in the intestines. The abomasum’s pH is usually between 3.5 and 4.0. The abomasal wall gets protection from acid damage from the mucous secreted from the abomasum’s chief cells.

The Ruminant’s Small and Large Intestine

Other sites of nutrient absorption are the small and large intestines. The tube-shaped small intestine can be 150 feet long. In a mature cow, its capacity is 20 gallons.

Digests that enter the small intestine combine with secretions that come from the liver and pancreas, It increases the pH from 2.5 to around 7 or 8. It’s necessary for the pH to increase for proper functioning of the small intestine’s enzymes.

Bile that comes from the gall bladder comes into the first part of the small intestine (called the duodenum) to help with digestion. The small intestine is responsible for active nutrient absorption. This includes rumen bypass protein absorption. There are many villi (projections that look like fingers) on the intestinal wall.

The intestinal surface area help with nutrient absorption. Contractions in muscles help to mix the digesta and make it travel to the next section. The large intestine will also take water from the material that goes through it. It then moves the rest of the material to the rectum as feces.

Grains and the Ruminant Digestive System

While sheep are well-known for loving grain, you need to be careful that they don’t get carried away.

It’s better to give sheep whole grain, as this will make sheep do the grinding of the grain themselves, adding more saliva.

While any kind of grain can cause digestive upsets in sheep, whole grain is less likely to do this than processed grain.

Always remember how crucial forage is in the sheep’s diet. It is necessary for the rumen to continue functioning as it should. Forage should always play a prominent part in your flock’s diet.

When it comes to minerals, be aware that too much copper can be lethal for sheep. Some of the major minerals needed by sheep include sodium, phosphorus, calcium, magnesium, and sulfur. Sheep require trace minerals too. Consult with a veterinarian for advice on the specific nutritional requirements of your sheep. Individual animals may have special nutritional needs.